[Greetings, friends, from Austin! As I continue trying to write my first fiction book, I am diving back into the lectures that Brandon Sanderson does for his science fiction and fantasy class at BYU every year. Several videos from past years are on his YouTube, with this year’s lectures (now through week 3) being released one week at a time. (I’ve watched the classes before, but going through while knee-deep in writing a fiction book is proving quite useful.)

At the start of his class, Sanderson identifies three things that must be determined when writing a fiction story: character, setting, and plot. Over the last month, I have taken time to outline each of these categories for my book, using an outline, a vision board, a fantasy map, and a family tree to help me visualize.

Throughout the years, I’ve watched several storytelling lectures and read many books on the topic, collecting my fair share of lessons from the writers I admire: J.R.R Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, J.K. Rowling, Brandon Sanderson, Neil Gaiman, and Stephen King. I’ve written one article previously, “On Writing,” in a similar vein, but today, I begin sharing a view of my favorite storytelling mental models and frameworks.

In this first installment of what will be an ongoing storytelling series, I want to touch on a couple plot building methods. When writing my second book (History of the Hero), I spent a great deal of time and energy studying and thinking about the Hero’s Journey, influenced by Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces. It’s a brilliant framework that storytellers used long before there was a formula for people to follow. The temptation for the modern storyteller (myself included) is to follow the Hero’s Journey a little too rigidly as if it gives us boxes to check. But to follow the structure too closely (or too literally) is to corrupt it. When we try too hard to make our stories map neatly on the Hero’s Journey, the story (it seems to me) becomes stale. To rely too much on hitting all the steps is to squeeze all magic and imagination out of the story itself; there must be space for the story to move and breathe and take on a life of its own.

How much and how closely should we follow the Hero’s Journey for our structure, and when should we liberate ourselves from it? When might other plot-making methods serve us better? How much should we free ourselves from form entirely and let our imagination run wild? That is the balance I am trying to strike in my own story… a balance that is not so easy!

As Sanderson highlights in his class, there are several ways to structure a plot. There is no one-size-fits-all, but there are some general patterns or themes that must be present for the story to make sense and register as a good story with the audience. To that purpose, I start with my first installment on storytelling, highlighting some of the key frameworks and tools that one can use when recognizing or replicating patterns of stories.1

It is to that end that we devote the rest of today’s essay.]

There are many ways to tell a story. But not an infinite number of ways. For a story to be coherent, it must follow specific rules and contain certain elements. For it to satisfy and engage the reader, still other things must be present. From Aristotle’s Poetics to Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces, thinkers for thousands of years have tried to identify and distill what ingredients must go in the Cauldron to make a soup worth savoring.

When it comes to story structure—the order in which plot events are told—most stories (at least in the West) contain a few classic frameworks: The Three-Act Structure, Freytag’s Pyramid,2 the Hero’s Journey, and Dan Harmon’s Story Circle.

We start with the two that most of us are already familiar with: the classic three-act structure and the Monomyth (i.e., the Hero’s Journey most famously outlined by Campbell).

The Three-Act Structure

The three-act structure is the most common technique for writing stories taught to the English-speaking world. To the extent you took a creative writing class in the United States growing up, chances are that you learned to fit your story into the three-act structure with its beginning, middle, and end (a.k.a. its setup, confrontation, and resolution, or exposition/inciting incident, rising action/midpoint, and climax/denouement).

It is an effective structure that poets and playwrights have used for thousands of years. (Shakespeare technically used a five-act structure, but his five acts followed the same general framework as the three-act structure.) Aristotle identified the three-act structure as one of the five elements of tragedy in his Poetics.

These principles being established, let us now discuss the proper structure of the Plot, since this is the first and most important thing in Tragedy.

Now, according to our definition, Tragedy is an imitation of an action that is complete, and whole, and of a certain magnitude; for there may be a whole that is wanting in magnitude. A whole is that which has a beginning, a middle, and an end. A beginning is that which does not itself follow anything by causal necessity, but after which something naturally is or comes to be. An end, on the contrary, is that which itself naturally follows some other thing, either by necessity, or as a rule, but has nothing following it. A middle is that which follows something as some other thing follows it. A well constructed plot, therefore, must neither begin nor end at haphazard, but conform to these principles.

Again, a beautiful object, whether it be a living organism or any whole composed of parts, must not only have an orderly arrangement of parts, but must also be of a certain magnitude; for beauty depends on magnitude and order. Hence a very small animal organism cannot be beautiful; for the view of it is confused, the object being seen in an almost imperceptible moment of time. Nor, again, can one of vast size be beautiful; for as the eye cannot take it all in at once, the unity and sense of the whole is lost for the spectator; as for instance if there were one a thousand miles long. As, therefore, in the case of animate bodies and organisms a certain magnitude is necessary, and a magnitude which may be easily embraced in one view; so in the plot, a certain length is necessary, and a length which can be easily embraced by the memory. The limit of length in relation to dramatic competition and sensuous presentment, is no part of artistic theory. For had it been the rule for a hundred tragedies to compete together, the performance would have been regulated by the water-clock,—as indeed we are told was formerly done. But the limit as fixed by the nature of the drama itself is this: the greater the length, the more beautiful will the piece be by reason of its size, provided that the whole be perspicuous. And to define the matter roughly, we may say that the proper magnitude is comprised within such limits, that the sequence of events, according to the law of probability or necessity, will admit of a change from bad fortune to good, or from good fortune to bad.3

Aristotle thought each act should be bridged by a beat or rhythm that sends the narrative in a different direction. Stories, he thought, ought to be an unbroken chain of causes and effects with a logical starting point and ending point, neither too short nor too long. Just like symmetry makes objects beautiful, Aristotle thought this plot structure is what made stories beautiful. Reading Aristotle through a Platonic lens, we might even say that Aristotle was trying to get to the Form of story itself and the excellence of the story depended on the degree to which it followed the Form.

As a plotmaking device, the three-act structure is simple to follow and effective—an initial and effective filter when outlining the general arc of a plot. But it tends to ignore (at least in its simplest form) the development of characters. For that, we look at the Hero’s Journey (and Harmon’s Story Circle).

The Hero’s Journey (Joseph Campbell)

When Joseph Campbell, a professor of literature at Sara Lawrence College, looked across cultures, what he found was remarkable: in every age and culture, from ancient Mesopotamia to our modern Western World, most stories appear to share a similar arc.

Campbell called this pattern (borrowing from James Joyce) the Monomyth—a single myth told in a thousand different ways, showing a single hero with a thousand different faces. Distilled in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell’s Monomyth is now synonymous with the Hero’s Journey seen in the stories we’re most familiar with, like George Lucas’ Star Wars (which Lucas said, expressly, was inspired by Campbell’s work) or Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.

At its simplest, the Hero’s Journey is a common narrative archetype—or story template—that involves a hero who starts in an Ordinary World (or world of the status quo), goes on an adventure, learns a lesson or two (or three), wins a victory with their newly gained knowledge, and then returns home transformed from the whole ordeal. It’s in the Epic of Gilgamesh, the tales of King Arthur, and the exploits of Harry Potter. Here’s how Campbell summarizes it in The Hero with a Thousand Faces:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder; fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won; the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.4

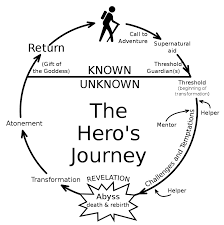

The Hero’s Journey is almost always depicted as a circle, partially because once one journey is complete, another comes knocking, and partially because the circle symbolizes wholeness (and the Hero’s Journey, in the end, is about integration and expansion of Self). In its various forms, the Hero’s Journey can have as many as seventeen steps (as in Campbell’s original formulation) or as little as four.

Wanting to simplify the Hero’s Journey to make it more accessible, Disney executive Christopher Vogler streamlined it into 12 steps in The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers:

The Ordinary World. The story begins with the hero’s status quo.

The Call of Adventure. Something (or someone) pulls the hero to leave home.

Refusal of the Call. The hero resists (or hesitates to answer) the pull.

Meeting the Mentor. The hero meets someone who prepares them for what lies ahead (often a parental figure, teacher, or other wise person).

Crossing the First Threshold. The hero steps out of their comfort zone and enters the unknown.

Tests, Allies, Enemies. The hero (protagonist) faces trials and perhaps finds new friends to help overcome them.

Approach to the Inmost Cave. The hero gets close to their goal.

The Ordeal. The hero meets (and overcomes) their greatest challenge yet.

Reward. The hero finds (and seizes) something important they were after.

The Road Back. The hero realizes that achieving their goal is not the final hurdle.

Resurrection. The hero faces a final challenge that forces them to use everything they’ve learned on their journey.

Return with the Elixir. Having triumphed, the matured hero returns to their old life, and their village is better for it (or peace is restored).

If the three-act structure is too vague in its extreme, then the Hero’s Journey might suffer from the opposite problem—being too specific and detailed. With its various rules and steps, it can start to feel like a checklist that we must hit. Perhaps a mentor in the first act doesn’t make sense, but we feel obligated to force one in. Or a final hurdle doesn’t make sense after receiving the reward because the hero will soon be sent on a different, separate quest. The risk with the Hero’s Journey and following it too closely is that we can get bogged down trying to capture and incorporate each element of the Hero’s Journey. If we over-rationalize the process, the story loses some of its magic.

Of course, it is also possible to make the opposite mistake, going to great lengths to be a contrarian and subvert the Hero’s Journey too intentionally or ignore it entirely. We must remember that these structures are pattern-recognition tools, telling us more about human nature, generally, and how people experience stories through the lens of their personal lives. The reason these structures work is because people recognize the truth of them from their everyday experiences. We ignore these patterns at our peril.

The Story Circle

In the late 1990s, screenwriter and producer Dan Harmon, took Campbell’s Hero Journey framework and simplified it into his version called the “Story Circle.” At the time, he was writing screenplays and found that many of his colleagues had difficulty writing plots for television shows. In response, Harmon decided to codify what he thought was a way to reliably produce a coherent story that would resonate with the audience. That codification was the Story Circle, which comprises eight steps that roughly parallel parts of the Hero’s Journey. Those eight steps can be condensed as: You —> Need —> Go —> Search —> Find —> Take —> Return —> Change.

These steps (described by Harmon in a blog post here) can be briefly summarized as follows:

You

The cycle of character development starts here, with the character caught in the status quo and comfort zone where order reigns supreme. Every day is mundane, and the character has settled into a life of less than. Here’s what Harmon says about how to develop the “You” phase as a storyteller:

If there are choices, the audience picks someone to whom they relate. When in doubt, they follow their pity. Fade in on a raccoon being chased by a bear, we are the raccoon. Fade in on a room full of ambassadors. The President walks in and trips on the carpet. We are the President. When you feel sorry for someone, you’re using the same part of your brain you use to identify with them.5

Need

Something (a need) pushes the character out of the inertia of the status quo. It can be something they want to possess or something they want to avoid. Whatever it is, the desire compels the character to take action. Here’s Harmon:

This is where we demonstrate that something is off balance in the universe, no matter how large or small that universe is. If this is a story about a war between Earth and Mars, this is a good time to show those Martian ships heading toward our peaceful planet. On the other hand, if this is a romantic comedy, maybe our heroine is at dinner, on a bad blind date.

We’re being presented with the idea that things aren’t perfect. They could be better. This is where a character might wonder out loud, or with facial expressions, why he can’t be cooler, or richer, or faster, or a better lover. This wish will be granted in ways that character couldn’t have expected.6

Go

Once the need (pull) or circumstance (push) launches the character out of the comfort zone, they cross the threshold and enter into the land of the unknown (chaos). Harmon explains it this way:

What’s your story about? If it’s about a woman running from a killer cyborg, then up until now, she has not been running from a killer cyborg. Now she’s gonna start. If your story is about an infatuation, this might be the point where our male hero first lays eyes on the object of his desire. Then again, if our protagonist is the object of a dangerous obsession, the infatuation could have been step 2 and this could be the point where the guy says something really, really creepy to her in the office hall. If it’s a coming of age story, this could be a first kiss or the discovery of an armpit hair. If it’s a slasher film, this is the first kill, or the discovery of a corpse.7

Search

In this phase, the things the hero encounters in the unknown require the character to acquire skills and learn how to survive (or thrive) in this new world. Harmon says this:

In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell actually evokes the image of a digestive tract, breaking the hero down, divesting him of neuroses, stripping him of fear and desire. There’s no room for bullshit in the unconscious basement. Asthma inhalers, eyeglasses, credit cards, fratty boyfriends, promotions, toupees and cell phones can’t save you here. The purpose here has become refreshingly - and frighteningly - simple…

We are headed for the deepest level of the unconscious mind, and we cannot reach it encumbered by all that crap we used to think was important.8

Find

After enough tests and trials have prepared the character, they eventually get what they were seeking, but it comes at a cost… or is not what they hoped it would be. It might even be that they had to fail at their quest. Following Campbell, Harmon describes this as “Meeting with the Goddess” and describes it this way:

Whatever you call it, this is a very, very special pivot point. If you look at the circle, you see I’ve placed the goddess at the very bottom, right in the center. Imagine your protagonist began at the top and has tumbled all the way down here. This is where the universe’s natural tendency to pull your protagonist downward has done its job, and for X amount of time, we experience weightlessness. Anything goes down here. This is a time for major revelations, and total vulnerability. If you’re writing a plot-twisty thriller, twist here and twist hard.9

Take

After the character takes or finds what they were after (or needed), often (though not always), new and unexpected losses follow the supposed victory. Harmon explains his understanding of what’s going on in this phase this way:

That’s because this half of the circle has its own road of trials - the road back up. The one down prepares you for the bed of the goddess and the one up prepares you to rejoin the ordinary world…

When you realize that something is important [or have the revelation from the Goddess meeting], really important, to the point where it’s more important than YOU, you gain full control over your destiny. In the first half of the circle, you were reacting to the forces of the universe, adapting, changing, seeking. Now you have BECOME the universe. You have become that which makes things happen. You have become a living God.

Depending on the scope of your story, a “living God” might be a guy that can finish changing a tire in the rain. Or, in the case of Die Hard, it might be a guy that can appear on the roof, dispatch terrorists with ease and herd 50 hostages to safety while dodging gunfire from an FBI helicopter.10

Return

The character then returns to where they started (or somewhere representative of where they started). Harmon calls this phase “Bringing it Home:”

For some characters, this is as easy as hugging the scarecrow goodbye and waking up. For others, this is where the extraction team finally shows up and pulls them out… For [still] others, [the journey is] not so easy, which is why Campbell also talks about “The Magic Flight.”

The denizens of the deep can’t have people sauntering out of the basement any more than the people upstairs wanted you going down there in the first place. The natives of the conscious and unconscious worlds justify their actions however they want, but in the grand scheme, their goal is to keep the two worlds separate, which includes keeping people from seeing one and living to tell about it.11

Change

This is the story’s resolution, where the lessons the character learned stay with them; the character has transformed and is now ready to reveal their new form.

They have been to the strange place, they have adapted to it, they have discovered true power and now they are back where they started, forever changed and forever capable of creating change. In a love story, they are able to love. In a Kung Fu story, they’re able to Kung all of the Fu. In a slasher film, they can now slash the slasher…

One really neat trick is to remind the audience that the reason the protagonist is capable of such behavior is because of what happened down below. When in doubt, look at the opposite side of the circle. Surprise, surprise, the opposite of (8) is (4), the road of trials, where the hero was getting his shit together. Remember that zippo the bum gave him? It blocked the bullet! It’s hack, but it’s hack because it’s worked a thousand times. Grab it, deconstruct it, create your own version. You didn’t seem to have a problem with that formula when the stuttering guy (4) recited a perfect monologue (8) in Shakespeare in Love. It’s all the same.12

It’s worth noting, at this point, that these various frameworks—the Three-Act Structure, the Hero’s Journey, and the Story Circle—are not competing methodologies but complementary lenses through which we can understand the architecture of stories. Like different maps showing the same territory from various angles, each framework illuminates particular aspects of storytelling. The Three-Act Structure gives us the broad strokes of narrative progression, the Hero’s Journey reveals the psychological depths of character transformation, and Harmon’s Story Circle offers a practical tool for modern storytellers. Used together, they form a toolkit for understanding how stories work and why they resonate so deeply with our lived experience.

Perhaps this is why studying story structure feels less like learning arbitrary rules and more like uncovering fundamental patterns of existence itself. When we analyze how stories and heroes move from ordinary worlds through challenges to transformation, we’re really studying the blueprint of human growth and change. These patterns persist across cultures and centuries not because storytellers are copying one another, but because they reflect something essential about how humans experience life and meaning. By understanding these structures, we don’t just become better storytellers—we become more conscious participants in our own hero’s journey, better equipped to recognize the calls to adventure in our lives, face our ordeals with courage, and return transformed. In this way, story structure isn’t just a guide for writing; it’s a map for living.

You know all of this instinctively. You are a storyteller. You were born that way.

(Dan Harmon)

—

P.S. Speaking of storytelling and meaning, here’s one of my favorite verses in the Bible:

For we are God’s handiwork, created in Christ Jesus to do good works, which God prepared for us to do.13

I have said before, and continue to believe that there is a work of sorts… a story (or many stories)… that is set inside us before birth. It is our job to unearth that work and then bring it forth. That is the soul’s dream and the life’s purpose. To discover the good works put in us by God’s handiwork and spend ourselves in the worthy cause of sharing it in service to the world. To do that is to live a life of maximum meaning.

—

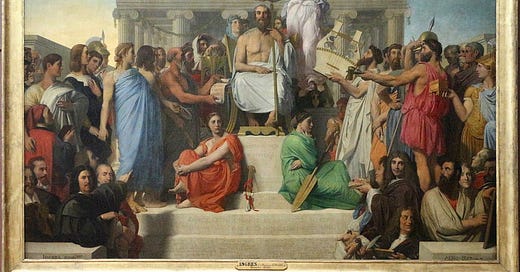

P.P.S. The following people are depicted in the picture that headlines this post (The Apotheosis of Homer): Homer, Herodotus, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Menander, Demosthenes, Apelles, Raphael, Sappho, Alcibiades, Virgil, Dante Alighieri, Horace, Peisistratos, Lycurgus of Athens, Torquato Tasso, William Shakespeare, Nicolas Poussin, Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux, Pierre Corneille, Jean Racine, Molière, François Fénelon, Cassius Longinus, Luís de Camões, Christoph Willibald von Gluck, Alexander the Great, Aristarchus of Samothrace, Aristotle, Michelangelo, Phidias, Pericles, Socrates, Plato, Hesiod, Pindar, and Aesop.

There is a deeper question here that I will not address in this essay—that is, whether we follow and enjoy the Hero’s Journey as a model because it is true to life in some fundamental way or if there is some other reason that we find it entertaining. Jung thought that myths were how the soul educated itself about the nature of reality itself—that the stories that welled up from the unconscious vapors contained lessons for our spiritual enlightenment. Aristotle thought Poetry (or mythology) was “a more philosophical and a higher thing than history: for poetry tends to express the universal, history the particular.” (Aristotle, Poetics, Book IX.)

We won’t spend time on Freytag’s Pyramid for two reasons: (1) it’s essentially a way of thinking about the classic three-act structure in the form of a pyramid (rise, climax, fall); and (2) the structure is used far less than it once was, as modern audiences have a much smaller appetite for true tragedies these days. The method is named after the 19th-century German novelist and playwright, Gustav Freytag (1816-1895) and was his five-point structure based on the classical Greek tragedies of Sophocles, Aeschylus, and Euripides.

Aristotle, Poetics, Book VII.

Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, p. 30.

Dan Harmon, Story Structure 104: The Juicy Details, Channel 101 Wiki (“Story Structure”).

Story Structure.

Story Structure.

Story Structure.

Story Structure.

Story Structure.

Story Structure.

Story Structure.

Ephesians 2:10.

While reading the second and third frameworks, one idea or insight began to form in my mind: the incidents from my life, which I often share with others as stories, seem to follow similar patterns. The ordinary world (where things aren’t going well), followed by the call to adventure (initially ignored or hesitated upon), an unexpected event, a test of endurance, just about to lose but ultimately winning, and then returning home, changed by the lessons learned.... A real-life story of mine that comes to mind is "13 Feb: The Day of Adventure, Hope, and Coincidence" (link: https://open.substack.com/pub/optinihilist/p/13-feb-the-day-of-adventure-hope).

In this story, I wasn’t consciously aware of these rules, patterns, or frameworks, yet I somehow acted them out. And the same seems to hold true for any anyone or any real-life story—past or present, across any culture—that is worth reading and sharing.

As I read this passage of yours, my initial assumptions became even clearer. These patterns aren’t just structures used to craft stories—they are the "fundamental patterns of existence itself." Here’s the passage from your essay that I’m referring to:

"Perhaps this is why studying story structure feels less like learning arbitrary rules and more like uncovering fundamental patterns of existence itself. When we analyze how stories and heroes move from ordinary worlds through challenges to transformation, we’re really studying the blueprint of human growth and change. These patterns persist across cultures and centuries not because storytellers are copying one another, but because they reflect something essential about how humans experience life and meaning. By understanding these structures, we don’t just become better storytellers—we become more conscious participants in our own hero’s journey, better equipped to recognize the calls to adventure in our lives, face our ordeals with courage, and return transformed. In this way, story structure isn’t just a guide for writing; it’s a map for living."

I’m currently working on writing a short fictional story, and reading this essay of yours has already been—and will continue to be—incredibly educational for me.