On Sloth

The Besetting Sin of Our Age

[Greetings, friends, from Austin! I come, first, asking for your forgiveness. Today, I am moving from the apartment I’ve occupied for the last three years and into a home, so most of my books are imprisoned in boxes prepared for transit. This means many (but not all!) of the books I could potentially pull from are stored away and out of reach, making this essay a bit of a wildcard.

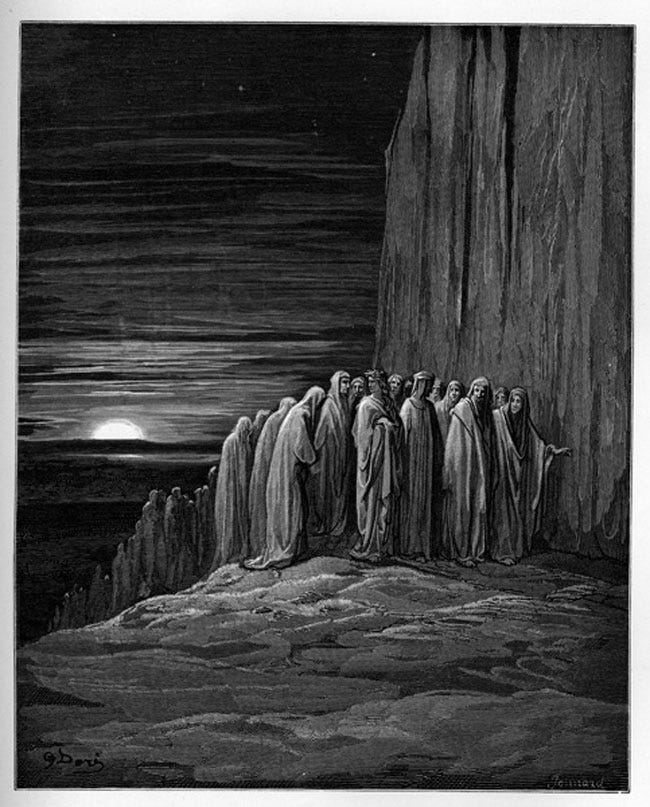

Of the books that have managed to escape the accumulation of dust, Dante’s Purgatory is the one most consuming my thoughts currently. This is partially because I just decided (and announced) that I would be teaching a free six-week course on Purgatory via Zoom starting April 1. The class is an extension of the six-week course I did on Dante’s Inferno earlier this year (on YouTube here). If you want to join the Zoom class sessions (Mondays at 6 PM CT) or just receive the outline, you can respond to this email, and I will put you on the list!

The other reason Dante is at the forefront of my thoughts is that the season of spring aligns with the story. One of the less-attended-to facts of Purgatory is that it begins on the morning of Easter—the day, among Christians, which commemorates Christ’s resurrection. (For reference, Dante’s first part of the poem, Inferno, starts on Good Friday—the day which honors the anniversary of Christ’s crucifixion—and his final installment, Paradise, begins on the Wednesday following Easter.)

In Inferno, the principle ethic at work was the idea of contrapassum (Latin for “suffer the opposite”)—souls cut off from God are eternally punished in death by the sins they committed in life (see On Eternal Justice). In Purgatory, the ruling principle is restoration—Purgatory is the mountain that liberates souls warped by the world… the winding road that unwinds the twisted so they may once again stand upright. In each of the Seven Terraces of Purgatory (one for each of the Seven Deadly Sins), we meet souls forced to learn the counteracting virtue of whatever sin made them incurvatus in se (bent in on oneself) in life.

On the Fourth Terrace, Dante and Virgil find the slothful—those who lacked zeal for the Good. It is to that particular sin, and why it is the one that besets our age, that I devote the rest of today’s essay.]

The Sin of Sloth (Acedia)

Sloth, the characteristic sin of our age, is the most difficult to define and label a sin. Our modern conception of the idea is often associated with laziness and used to describe those with an allergy to “hard work.” But sloth isn’t the opposite of industry; it is the opposite of enthusiasm… it is an indifference toward the True, Good, and Beautiful. Thus, someone stuck in a cycle of endless activity is equally as guilty of the sin of sloth as the one who does nothing but sleep.

The word “sloth” is a translation of the Greek akidía and the Latin acedia (meaning “without care” or in an inert state). In the Iliad, the ancient Greek Homer uses the term to describe (1) soldiers heedless of a comrade,1 and (2) the neglected body of Hector.2 By the early 5th century and on through the Middle Ages, the term became a technical one in Christianity, referring to a failure to love God with adequate fervor—allowing oneself to drift into a sort of indifference toward spiritual pursuits. “Sloth is a ‘sluggishness of the mind which neglects to begin good.’ … it destroys the spiritual life … on account of the flesh utterly prevailing over the spirit.”3

When we meet Dante, the pilgrim, in the Inferno, there is a case to be made that sloth of this type was not only a punishable in Purgatory but also Dante’s chief sin in his own life. In the opening lines of the Inferno, we find a Dante who had wandered from the straight and true path—he had fallen asleep at the wheel of his soul and lost track of where he was headed. By the time he arrives in the deepest pit of Hell and is told to “Behold Dis,” we learn this entire journey is about the pilgrim remembering to hold his soul at attention.

When we finally meet the slothful in Canto XVIII of Purgatory, Dante has received several corrections from Virgil (and one from Cato), who notice Dante’s tendency to linger—to delay—longer than he ought. In this way, Dante is like the folk on Purgatory’s Fourth Terrace “whom the fiery sting of love / makes up for [their] omission and delaying / when perhaps [they] were tepid in good works.”4 These are the first two types of sloth Dante introduces to us: those who never started and neglected good works entirely and those who delayed their pursuit of the Good.

At the end of Canto XVIII, we find a third category of the slothful: those who abandon a good work before it is finished—those impatient in their pursuit of the Good. In this category, Dante gives two examples of this type of sloth:

And he who was my help in every need

said, ‘Turn this way and see the two who come,

giving acedia the bite of blame.’

Behind the rest they called, ‘None were alive

of all for whom the Red Sea parted, when

at last the Jordan saw his heirs arrive,’

And, ‘Those who could not bear the toil and strife

with the son of Achises to the end

gave themselves up to an inglorious life.’5

The Besetting Sin of Our Age

When I say that ours is an age of sloth it is this neglect of, or disloyalty to, the spirit— indifference toward the things that truly matter—that I am gesturing at. And by saying ours, I am, for the most part, referring to those of us who live in the United States—where the economic machines of late-stage capitalism constantly try to suck individuals into the barrenness of a busy, or should I say slothful, life.

If the besetting sin of modernity is pride (an inordinate confidence in know-it-all reason), then that of postmodernity is sloth, a despairing indifference to truth. Someone who believes in nothing and lives for nothing might as well be asleep. Sloth is the ultimate sin of omission: sloth sits still, unmoved by anything real.

…

The sad truth is that many of us are, at best, only half awake. We think we’re engaged with the real world — you know, the world of stock markets, stockcar racing, and stockpiles of chemical weapon — but in fact we’re living in what Lewis calls the ‘shadowlands.’ We think we’re awake, but we’re really only daydreaming. We’re sleepwalking our way through life — asleep at the wheel of existence — only semi-conscious of the eternal, those things that are truly solid that bear the weight of glory.6

For those familiar with the work of Josef Pieper, this conjures a recollection of his lament for the loss of true leisure in the capitalistic society. True leisure is not the laziness that most modern Western folk believe it to be; it is a freedom from what you do for money, which makes room for the pursuit of higher spiritual goods. True leisure is what makes space for magnanimity. But today’s (Western) culture is motivated predominantly not by movements of the heart and soul but by how much it can get done in a day. This is why sloth is the besetting sin of our age.

Four years ago, it was undoubtedly my chief sin. At that time, I was an associate at a large law firm in Minneapolis, working in Private Equity Mergers & Acquisitions. I answered emails and pushed paper for upwards of 12 hours a day. I had little time for anything except work. Nobody would say I was lazy, but the sin of sloth most certainly had a hold on me.

Perhaps you, too, recognize some sloth in you and now find yourself asking what to do about it.

In Dante’s Purgatory, the cure prescribed to souls who suffered from sloth in life is to race around the terrace shouting famous examples of their vice (sloth) and its opposite virtue (zeal). We see them, “a rage of dust … swing[ing] their paces like a scythe … galloping for goodwill and righteous love…” shouting:

‘Mary ran to the hill country in haste!’

‘To conquer Lerida Caesar slashed Marseilles,

then ran to bend the enemy’s neck in Spain!’

‘Come on, come on, don’t let time slip away

for lukewarm love!’ cried those who ran nearby.

‘Zeal in well-doing makes grace green again!’7

I don’t think we need to dash about and shout ancient examples of sloth and zeal to heal ourselves of sloth. Yet what the souls in Purgatory do outwardly, we can do inwardly. We can shift our orientation toward the spirit through reflection and attention. Many of us have convinced ourselves that we are not guilty of sloth because we are not lazy. But are we properly oriented toward and attending to the things that matter? Or are we spending our lives distracted by meaningless things? Are we sleepwalking through life, or can we genuinely say that we are giving the best of our time, attention, and energy to the things that are highest?

If not, it might be time to make a change. It doesn’t need to be a big one—like leaving your job or your city. It just needs to be one that takes back energy from meaningless things that steal it. Maybe it’s writing, reading, or journaling first thing in the morning before opening the apps on your phone. Maybe it’s making yourself unavailable at work for larger chunks of time than you are comfortable doing. Whatever it is, just make sure it tends to the spirit.

‘Come on, come on, don’t let time slip away

for lukewarm love!’ ...

‘Zeal in well-doing makes grace green again!’

In Book XIV of the Iliad, Homer writes “their troops spared nothing, pitching in” to shield a fallen Hector from being finished by the Acheaens. (Fagles translation, line 503). Here, we see the troops do the opposite of acedia by sparing nothing in their protection of Hector.

In Book XXIV of the Iliad, when Priam comes to beg Achilles to return the body of his son, Hector, Priam says “Don’t make me sit on a chair, Achilles, Prince, / not while Hector lies uncared-for in your camp!” (Fagles translation, lines 648-650). Here, acedia is the act of not caring for the body of Hector—not tending to the thing that ought to be tended to.

St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Second Part of the Second Part, Question 35, Article 3, available here: https://sacred-texts.com/chr/aquinas/summa/sum290.htm.

Dante, Purgatory, lines 106-108 (Anthony Esolen translation). Kevin Vanhoozer, In Bright Shadow: C.S. Lewis on the Imagination for Theology and Discipleship, available here: https://www.desiringgod.org/messages/in-bright-shadow-c-s-lewis-on-the-imagination-for-theology-and-discipleship.

Dante, Purgatory, lines 130-138 (Anthony Esolen translation). The first example refers to the Israelites complaining after their exodus and thus being forbidden from reaching the Promised Land. The second comes from the Aeneid, where many of the weary Trojan women set fire to Aeneas’s ships and, as a result, failed to reach Rome, the long-desired destination.

Kevin Vanhoozer, In Bright Shadow: C.S. Lewis on the Imagination for Theology and Discipleship, available at: https://www.desiringgod.org/messages/in-bright-shadow-c-s-lewis-on-the-imagination-for-theology-and-discipleship.

Dante, Purgatory, lines 91-105 (Anthony Esolen translation).

Just found your writing from Paul Millerds new book. So glad I did. This quote hit hard!

"But sloth isn’t the opposite of industry; it is the opposite of enthusiasm… it is an indifference toward the True, Good, and Beautiful. Thus, someone stuck in a cycle of endless activity is equally as guilty of the sin of sloth as the one who does nothing but sleep."

This was a really powerful article. I liked the distinction between sloth and laziness, as I believe sloth in the modern age to be more akin to apathy. This has been a great reminder for me to make time for the things that truly matter to me.