[Greetings, friends, from Athens! If you read my last essay, you know I’ve been in Greece since last week. The last few days involved a road trip through Delphi (the mountain city where figures from Greek myth and philosophy would travel to consult the Oracle) and Meteora—a place full of stone pillars and monasteries built into mountains. The name Meteora derives from words meaning “lofty” or “elevated,” and the name “Meteoron” can be translated as “the rock suspended between heaven and earth.” It’s hard to describe how impossible it all seems. Below is one of the pictures I took with my drone.

The stone pillars rise out of forested valleys as if put there by giants. Science’s best explanation is that the rocks formed over thousands of years of earthquakes and erosions.

But since the 9th century, Christian hermits and monks have lived atop the stones that could only be reached by free climbing or accessed through a system of nets, pulleys, ladders, baskets, and ropes (roads and proper hiking paths didn’t appear until the 20th century). The monks spent 16 years building what would later become known as the “Great Meteoron,” the first and largest of the 24 monasteries built on the cliffs over the years.1

Why would the monks, without roads, go through such trouble to build monasteries into stones they could barely climb? It wasn’t simply to escape everyday life and put themselves beyond the reach of the day’s troubles and tensions; it was a belief they shared with the pagan Greeks that preceded them that in the high places, we are closer to God.

So, with that in mind, it is to high places and the human sense of verticality that we devote the rest of (part 1 of) today’s essay. (Part 2 of this essay is devoted to the logoi spermatikoi and how the Greek Byzantines and early Greek Christians saw the Ancient Greeks as fellow tellers of truth.)]

God in High Places

All the most important things in Ancient Greek culture and civilization were placed or seen in the highest places. Mount Olympus, the tallest mountain in Greece, was where the gods resided. The Oracle of Delphi and her powers were accessible only between two towering rocks of Mount Parnassus. Sacred buildings and structures like the Temple of Athena (i.e., the Parthenon) or the Temple of Poseidon were always placed on high ground to overlook the surrounding city below.

This structure reflected the inner sense of verticality. Gods were higher beings than humans, so things erected in their honor ought to occupy higher physical places as well. By building houses for their gods in physical space, they attempted to bring the heavens down to earth while recognizing and respecting that there were forces greater than humans at work in the world.

This idea in Greece wasn’t limited to their architecture. Plato’s Republic begins with Socrates saying he went “down yesterday to the Piraeus with Glaucon.” This journey downward is symbolic of the trip out of the realm of knowledge and the forms and into the opinions of the masses (where might makes right and the truth is whatever people want it to be). This journey down to the Piraeus to start the Republic makes sense once the reader is introduced to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, which sees man’s journey toward knowledge represented by a movement from looking at shadows in a dark cave of ignorance to starting directly at the Sun of truth itself.

Of course, this idea structure is not uniquely Greek. Other cultures and traditions have a long history of meeting the divine in high places and seeing the world with verticality. In the Hebrew tradition, the most famous is Moses traveling to the top of Mount Sinai to receive the tablets with the Ten Commandments. Then there’s also the story in Genesis of Jacob’s Ladder, a ladder connecting heaven with earth with angels walking up and down. It even extends to places like Tanzania, where Mount Kilimanjaro guides say things “when you get to the top, you talk with angels.”2

When we think about this all symbolically, we see something like a universal intuition that to travel upward is to travel in the direction of the divine. The further up we go, the further in we go, until we come to see God face to face in the innermost place of our being.

All of this aligns with the Ancient and Medieval view (see On the Discarded Image) that saw life as something like a moving up and down a ladder. Consider Dante’s Divine Comedy, where each phase of Dante’s journey through Hell and Purgatory up to Paradise is arranged hierarchically. Within the Christian tradition, the idea was that the individual’s actions in life were either a movement upward toward Heaven or a movement downward toward Hell. Plato outlined the idea that we are souls whose wings have been clipped, and the purpose of life was to rise again to the realm of the sublime, the Latin root of which means “uplifted, high, or exalted.” (See On Nature.)

With these universal intuitions also came caveats and cautions attached to the upward pursuits of humans. Both the Greeks and the Hebrews had their tales warning of the fall that happens when people try to take for themselves what can only properly be accessed through invitation. This is the Tower of Babel in Genesis built by the Babylonians to “make a name for themselves” rather than to honor God, a process which results in God’s confusion of their speech and destruction of their project. This is also the story of Icarus and Bellerophon in Greek mythology, each of whom is struck down and destroyed for their prideful attempts to rise too high.

These cautionary tales leave us to wonder about the fate of the Western world, where the highest buildings are corporate headquarters and skyscrapers, shrines to consumerism, and the ambitions of man—attempts, once again, of man to make a name for himself. Could it be, as I ask in On That Hideous Strength, that we are in, or about to experience, our own Babel moment?

The Logoi Spermatikoi

Setting that question aside for now and speaking of things recognized across multiple cultures and traditions, one of the facts of history I find most fascinating is how the early Christians interpreted the teachings of Ancient Greek philosophers. I spent a lot of time excavating this part of history while reading and writing my first three books. Before Meteora, my knowledge of the topic was entirely secondhand—coming purely from what I had read in books. In the mountain monasteries, I saw the connection from the source itself for the first time, and to say the experience was special is to sell it unforgivably short.

The early church embraced the Ancient Greeks and pagan cultures. Just like the ancient Hebrew texts, the early Christians interpreted the works of the Ancient Greeks in light of Christian revelation, with ancient Greek mythology and philosophy pointing toward the same God as Christianity, even if only vaguely and without the benefit of complete revelation. This is what Simone Weil called “intimations” of Christianity (see On Intimations in Ancient Greece).

It is also what Jung called the logoi spermatakoi (or the seed of divine truth), which we encounter in almost all traditions. In a unique and unprecedented way, Greek philosophy, poetry, and science deeply penetrated the roots of truth. Recognizing the wisdom of the pre-Christ Ancient Greeks, St. Justin, the philosopher and martyr (165 AD) declared: “Whoever lived with prudence and logos (before Christ’s birth) is a Christian, even if he was considered to be an atheist, for instance, among Greeks, Socrates, Heraclitus and others like them.”

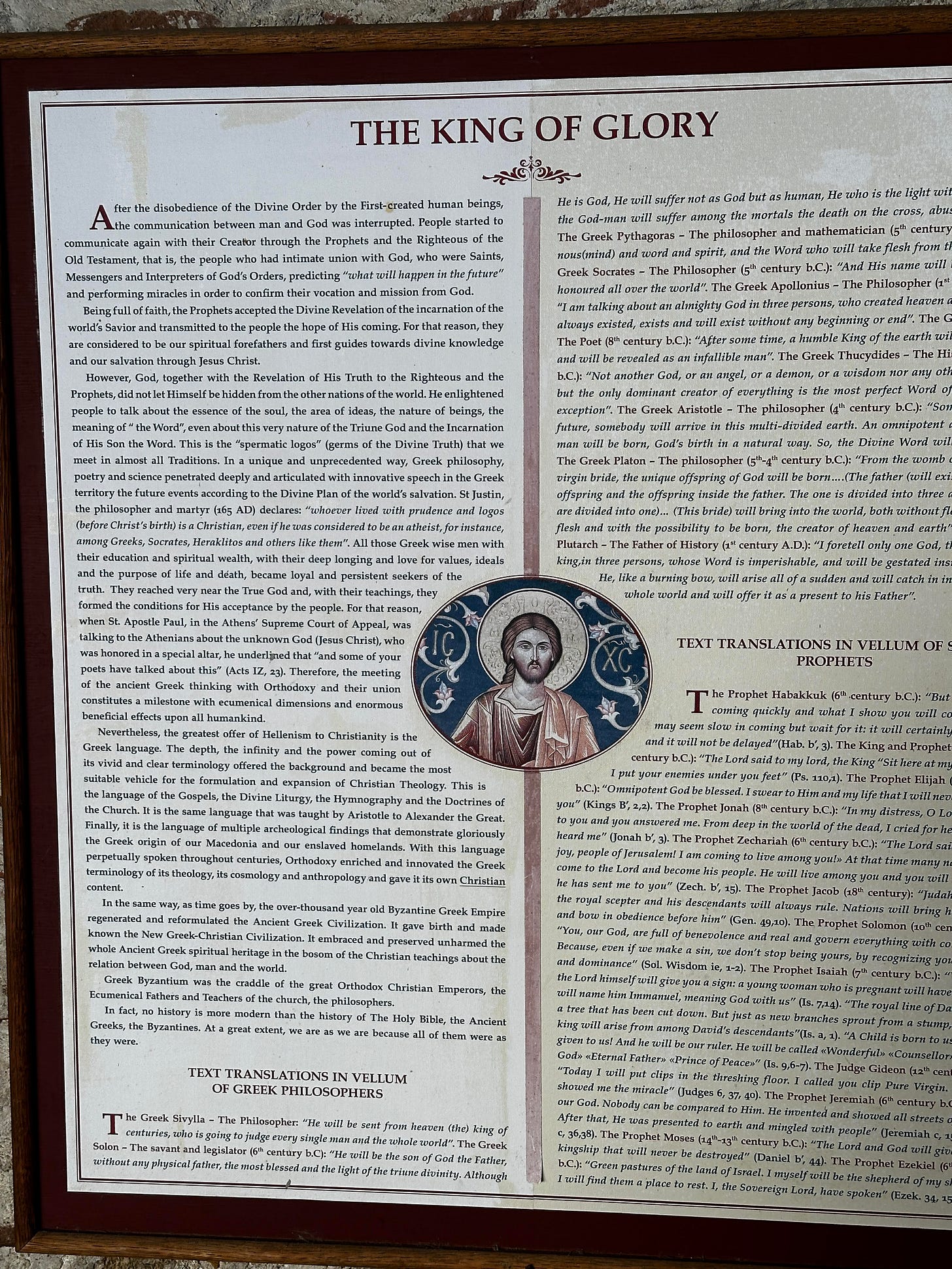

In the Great Meteoron, a fresco depicted this overlap of traditions. On one side of the icon was a troupe of ancient Greek philosophers and poets (Pythagoras, Solon, Plato, Socrates, Aristotle, Homer, etc… the left side of the picture below), and on the other side, there were the ancient Hebrew prophets (David, Solomon, Jonah, Isiah, Elijah, etc… the right side of the picture below).

As the description puts it: “[N]o history is more modern than the history of The Holy Bible, the Ancient Greeks, the Byzantines. At a great extent, we are as we are because all of them were as they were.”

Next to the fresco icon was a short description that summarized not only how the Greek Byzantines embraced Ancient Greeks but also attributed specific quotes prophesying the coming of a savior to each. (See below for the (almost) full description… sorry for the cut-off picture).

The description also quotes pre-Christ Hebrew prophets. I’ve included each quote below if you’d like to read them without zooming in and out of the photo. You’ll notice that each quote from Hebrew prophets has a specific citation, while those of the Greek philosophers and poets (unfortunately) do not. This leaves the question: did the Ancient Greeks actually say these things in texts preserved by the Greek Byzantines but have since been lost? Or do they represent the wishful thinking of Christian monks seeing what they wanted to see?

I don’t have the answer to that question (yet). In the meantime, enjoy the attributions:

SAVIOR PROPHECIES FROM GREEK PHILOSOPHERS AND POETS

The Greek Sivylla - The Philosopher: “He will be sent from heaven (the) king of centuries, who is going to judge every single man and the whole world.”

The Greek Solon - The Savant and Legislator (6th Century B.C.): “He will be the son of God the Father, without any physical father, the most blessed and the light of the triune divinity. Although He is God, He will suffer not as God but as human, He who is the light with human flesh; the God-man will suffer among the mortals the death on the cross, abuse and burial.”

The Greek Pythagoras - The Philosopher and Mathematician (5th Century B.C.): “God is nous (mind) and word and spirit, and the Word who will take flesh from the father.”

The Greek Socrates - The Philosopher (5th Century B.C.): “And His name will be known and honoured all over the world.”

The Greek Apollonius - The Philosopher (1st Century A.D.): “I am talking about an almighty God in three persons, who created heaven and earth. God always existed and will exist without any beginning or end.”

The Greek Homer - The Poet (8th Century B.C.): “After some time, a humble King of the earth will come to you and will be revealed as an infallible man.”

The Greek Thucydides - The Historian (5th-4th Century B.C.): “Not another God, or an angel, or a demon, or a wisdom nor any other substance, but the only dominant creator of everything is the most perfect Word of all, without exception.”

The Greek Aristotle - The Philosopher (4th Century B.C.): “Sometime in the future, somebody will arrive in this multi-divided earth. An omnipotent and infallible man will be born, God’s birth in a natural way. So, the Divine Word will take flesh.”

The Greek Plato - The Philosopher (5th-4th Century B.C.): “From the womb of a pure and virgin bride, the unique offspring of God will be born... The father (will exist) inside his offspring and the offspring inside the father. The one is divided into three and the three are divided into one) ... (This bride) will bring into the world, both without flesh and with flesh and with the possibility to be born, the creator of heaven and earth.”

The Greek Plutarch - The Father of History (1st Century A.D.): “I foretell only one God, the most high king, in three persons, whose Word is imperishable, and will be gestated inside a virgin. He, like a burning bow, will arise all of a sudden and will catch in in his nets the whole world and will offer it as a present to his Father.”

SAVIOR PROPHECIES FROM HEBREW PROPHETS

The Prophet Habakkuk (6th Century B.C.): “But the time is coming quickly and what I show you will come true. It may seem slow in coming but wait for it: it will certainly take place and it will not be delayed.” (Hab. b’, 3).

The King and Prophet David (10th Century B.C.): “The Lord said to my lord, the King “Sit here at my right until I put your enemies under your feet.” (Ps. 110,1).

The Prophet Elijah (8th Century B.C.): “Omnipotent God be blessed. I swear to Him and my life that I will never abandon you.” (Kings B’, 2,2).

The Prophet Jonah (8th Century B.C.): “In my distress, O Lord, I called to you and you answered me. From deep in the world of the dead, I cried for help and you heard me.” (Jonah b’, 3).

The Prophet Zechariah (6th Century B.C.): “The Lord said ‘Sing for joy, people of Jerusalem! I am coming to live among you!’ At that time many nations will come to the Lord and become his people. He will live among you and you will know that he has sent me to you.” (Zech. b’, 15).

The Prophet Jacob (18th Century B.C.): “Judah will hold the royal scepter and his descendants will always rule. Nations will bring him tribute and bow in obedience before him.” (Gen. 49,10).

The Prophet Solomon (10th Century B.C.): “You, our God, are full of benevolence and real and govern everything with compassion. Because, even if we make a sin, we don’t stop being yours, by recognizing your majesty and dominance.” (Sol. Wisdom ie, 1-2).

The Prophet Isaiah (7th Century B.C.): “Well then, the Lord himself will give you a sign: a young woman who is pregnant will have a son and will name him Immanuel, meaning God with us.” (Is. 714). “The royal line of David is like a tree that has been cut down. But just as new branches sprout from a stump, so a new king will arise from among David’s descendants.” (Is. a, 1). “A Child is born to us. A son is given to us! And he will be our ruler. He will be called «Wonderful» «Counsellor» «Mighty God» «Eternal Father» «Prince of Peace».” (Is. 9,6-7).

The Judge Gideon (12th Century B.C.): “Today I will put clips in the threshing floor. I called you clip Pure Virgin. Your Son showed me the miracle.” (Judges 6, 37, 40).

The Prophet Jeremiah (6th Century B.C.): “He is our God. Nobody can be compared to Him. He invented and showed all streets of science. After that, He was presented to earth and mingled with people.” (Jeremiah c, 15, Varuch c, 36,38).

The Prophet Moses (14th-18th Century B.C.): “The Lord and God will give birth to kingship that will never be destroyed.” (Daniel b’, 44).

The Prophet Ezekiel (6th Century B.C.): “Green pastures of the land of Israel. I myself will be the shepherd of my sheep, and I will find them a place to rest. I, the Sovereign Lord, have spoken.” (Ezek. 34, 15).

Some think that without these monasteries beyond the reach of the Ottoman occupation preserving the Greek academic, artistic, philosophical, and religious culture, Greek and Greek Byzantine culture might largely have disappeared and became an echo of Turkish culture with little knowledge or appreciation for its Hellenistic roots.

This line is delivered to my friend Joe Lindley in his upcoming documentary, “Ashes of the Mountain.”