[Greetings, friends, from Austin! This past weekend, I had the honor of participating in an event called “Hell on Hogsback” in Cleveland, Ohio. The event is a charity race with the option to spend 1-hr, 3-hr, or 12-hr running up and down a (steep) hill as many times as possible.

It’s put on by my friend and Founder of Sisu Sauna, Pete Nelson, to honor and raise funds for those affected by cancer. It started after Peter’s father’s battle with tongue cancer turned into a 12-hour fight under the knife of a surgery that involved a stroke a few years back. Since surgery, Pete’s dad has run 11 marathons and runs 12 hours during Hell on Hogsback to commemorate the number of hours in his surgery… the man is a remarkable example of the relentless spirit man is capable of. To summarize Seneca: a man like that could not stand upright unless propped up by the divine.

There’s a reason Pete’s sauna business bears the name that it does: Sisu. Sisu is a Finnish word without an English translation, which means something like:1

An unconquerable soul. A blend of grit and bravery, ferocity and tenacity, with the ability to keep fighting when most would quit. An indomitable spirit.

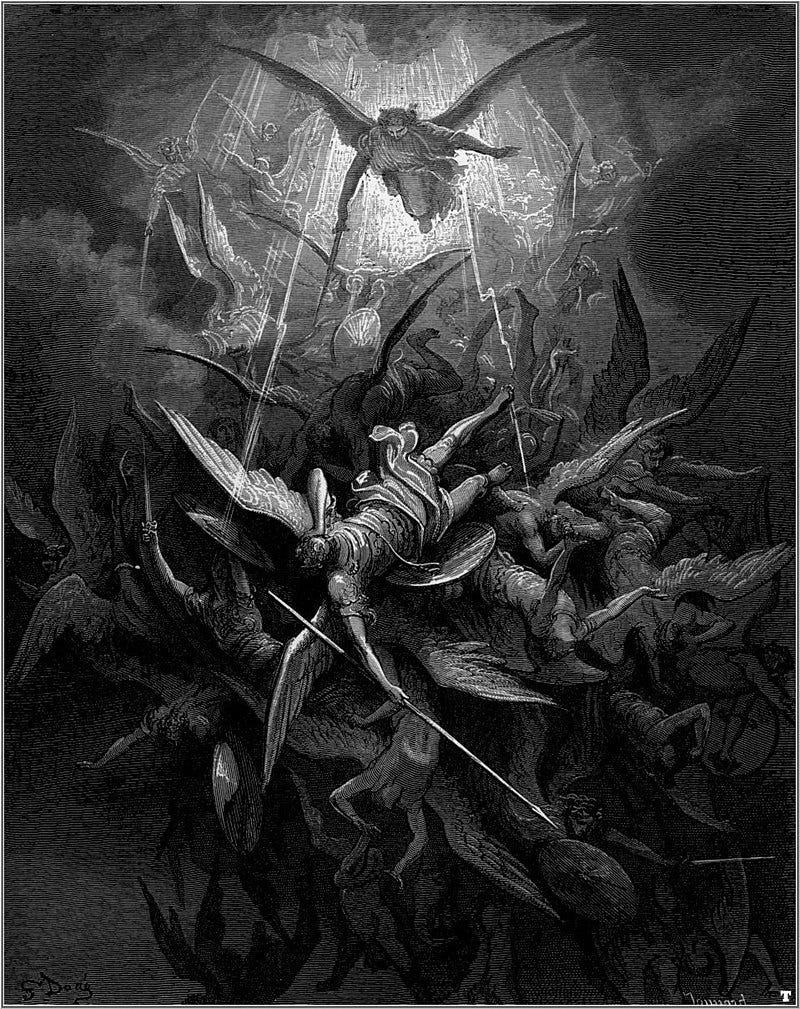

This word, the race, and a re-watching of the Lord of the Rings Trilogy last week has me reflecting on the spirit of endurance in the will of man… the invincible sunshine in the heart of humanity… and raging against the dying of the light.

It is to the long rebellion that keeps the eternal darkness at bay that we devote the rest of today’s essay.2]

After the Fellowship passes through Moria and arrives in Lothlórien, they come before Celeborn and Lady Galadriel. Delivering the news that Gandalf has fallen into the shadow at the hands of the Balrog, every elf in attendance disheartedly decries the “evil tidings.” “Gandalf was our guide, and he led us through Moria,” Frodo announces in honor of the great wizard, “when our escape seemed beyond hope, he saved us, and he fell.” 3

Aragorn proceeds to offer a summary of the Fellowship’s journey up to Lothlórien, and then Lady Galadriel reveals that the purpose of the Fellowship’s Quest is no secret—she and the King are aware of the Ring and their trip (though Gandalf has fallen) may not yet be in vain. For Celeborn, Lord of the Galadhrim, says Galadriel, is the wisest of elves and giver of gifts beyond the power of kings. Then she drops one of the most stirring and insightful lines in the entire Trilogy:

[Celeborn] has dwelt in the West since the days of dawn, and I have dwelt with him years uncounted; for ere the fall of Nargothrond or Gondolin I passed over the mountains, and together through ages of the world we have fought the long defeat… But even now there is hope left.4

With the words “long defeat,” Galadriel is referencing the slow fading of elves and men. Tolkien’s universe follows the pattern of the Anglo-Saxon and Pagan idea of Ragnarök… that the arc of time bends toward inevitable ruin and destruction. It is also the Classical idea of Hesiod that the lineage of mankind deteriorated as they fell further from their divine origins: progressing through the Golden Age, the Silver Age, the Bronze Age, the Age of Heroes, to the Iron Age.

This philosophical outlook and lens is, of course, in stark contrast to the purely evolutionist interpretation of history that says time is a steady upward march of improvement and moral progression toward utopia. The problem with that view, which many today now seem to hold, is not only that it stands in conflict with the Second Law of Thermodynamics, which says that the natural state of everything is entropy—that in the absence of distinct and direct effort to preserve, things tend toward decay—but it also at odds with the experience of humanity, which saw some of history’s worst atrocities in the Nazi Germany, Communist China, and Soviet Russia of the 20th century.5

This is part of the “Myth of Moral Progress” that Tolkien gestured at with this idea that history is a long defeat. When this is where the story ends, this is how you end up with the Norse stories of Ragnarök or the Greek myth of Sisyphus—who, as Ovid tells it in Metamorphosis, “dost either push or chase the rock that must always be rolling down the hill again” for all eternity.

For writers like Albert Camus, this is where the story of humanity begins and ends. Without hope for anything other than the eternal struggle, we humans are destined to progress through life with the same futility as Sisyphus with his rock on the hill. The best we can do is “imagine Sisyphus happy.” 6

But for Tolkien, this is not where the story ends, for we see in story and reality some glimpses at the possibility of a final victory.

Actually I am a Christian, and indeed a Roman Catholic, so that I do not expect ‘history’ to be anything but a ‘long defeat’ – though it contains (and in a legend may contain more clearly and movingly) some samples or glimpses of final victory.7

Tolkien’s story of Middle Earth takes the ancient notion of inevitable decline and weaves into it a golden thread that is fundamentally Christian: eucatastrophe. As a concept created (or at least coined) by Tolkien, he describes it this way in a letter to his son, Christopher:

[T]he sudden happy turn in a story which pierces you with a joy that brings tears (which I argued it is the highest function of fairy-stories to produce). And I was there led to the view that it produces its peculiar effect because it is a sudden glimpse of Truth, your whole nature chained in material cause and effect, the chain of death, feels a sudden relief as if a major limb out of joint had suddenly snapped back. It perceives — if the story has literary ‘truth’ on the second plane (….) — that this is indeed how things really do work in the Great World for which our nature is made.8

We see examples of this throughout Lord of the Rings, mirroring the pattern of ultimate victory of evil in the Book of Revelation. It is Isildur taking up the broken sword of his fallen father when all seems lost and slicing the Ring from Sauron’s finger, the arrival of the Eagles when there is no escape, the coming of reinforcements when the hour of doom is at hand, the falling of Gollum into Mount Doom just as it seems Frodo is about to fail.

These moments of eucastrophe are made possible by the characters’ insistence to keep fighting even when all seems helpless, which we find on every page of parchment and in every line of ink throughout the Trilogy. The rally of dwarves, elves, and men sacrificing themselves in battle under a common banner. Aragorn declaring that if men must die then he will die as one of them… Frodo sparing Gollum despite the ongoing threat to his personal safety… Boromir and Faramir offering themselves as sacrificial decoys in war. Time after time, the Fellowship and those clearing the way fight despite “hope without guarantees:”

Even if we believe that the lights go out when our heart stops, it is hard not to be attracted to this strange morality that leaves Boromir fighting off hordes of orcs in order to protect two lowly hobbits (without success, as it turns out) or King Theoden leading a seemingly hopeless charge into final glorious battle. Tolkien has made his stand against the utilitarian spirit of the age, not through self-righteous diatribes, but through story after grand story of characters living in testimony to inherent goodness. Characters consistently make potentially catastrophic decisions simply because they believe it is the right thing to do… ‘even if disastrous in the world of time.’9

We are moved by this morality because it touches a deep reality in our hearts… it sings of Heaven and vibrates the strings that connect us with eternity. It “produces its peculiar effect because it is a sudden glimpse of Truth.” In speaking to us, these offer reminders of our duty to resist decline and stand firm in our convictions of the True, Good, and Beautiful, on the hope that dawn will come again.

This is why it is the highest honor of our lives to fight the long defeat throughout the ages of the world. Because our world, like Middle Earth, is always on the edge of decay and needs those willing to deal love and hope through sacrifice.

Fighting the long defeat will not protect us from hurt and will often involve a temptation toward resignation. But we must not give in. We must constantly and continuously lean into a full and unapologetic engagement in life defensible before a Judge standing outside of time. To fight the long defeat is to risk “reputation” to speak the truth, be willing to lose wealth for what’s right, and keep a dogged pursuit of beauty regardless of recognition. It is a love for all worthy things that “stand in peril,” undeterred by success, timetables, or ambitions, preserving them for the unborn millions.

That is our task.

But this I will say to you: your Quest stands upon the edge of a knife. Stray but a little and it will fail, to the ruin of all. Yet hope remains while all the Company is true.

(J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring, p. 357).

During a conversation with Pete about the origins of the Sisu name, he told me I needed to watch the 2022 movie bearing the name as the title (“Sisu”). Set during the Lapland War between Finland and Nazi Germany towards the end of World War II, the almost deliriously gory story follows the legendary Finnish Army commando—nicknamed Koschchei (the “Deathless”) by Stalin’s Red Army—as he goes through Hell and High Water to defend himself from being robbed and murdered by a Nazi platoon pursuing him.

This essay would not have been possible without this essay. After reading it many years ago, along with this essay on Lincoln, it is probably one of the articles I think about most often.

J.R.R. Tolkien, Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (the “Fellowship of the Ring”), p. 356.

The Fellowship of the Ring, p. 357.

To say that we are always getting “better” and more “enlightened” is like saying we can understand the meaning and original intent of the Constitution better than the Framers at the Constitutional Convention… it is, in my view and as someone who believes in a created universe, nonsensical. As the ones furthest away from the point of creation, our being is the most diluted; our memory getting more foggy by the minute.

Albert Camus, Myth of Sisyphus. Even though he would deny it, I think Camus’ idea here of imagining Sisyphus happy (which is what we have to do because nothing suggests that Sisyphus was, in fact, happy) is a fundamentally Christian idea that requires hope… hope that something is happening internally or externally as a result of the struggle that makes life worth living, even if we’re unable to discern and even if the hope is a hope without guarantees. I once read somewhere of someone saying that Camus, if he had lived long enough, would have become one of the most convincing Christians of his day… and I tend to agree.

Tolkien Letters, Letter 195.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien (“Tolkien Letters”), Letter 89.

Andrew Barber, Tolkien and the Long Defeat.

Inspiring!