[Greetings, friends, from Austin! Something about the end of winter (…even in Texas!) always makes me contemplate whether I’m on the right track. Many of my most brutal battles with Resistance come in these months. This year has been no different.

Perhaps it’s less sunshine. Perhaps it’s the dead vegetation. Or perhaps it’s just the natural rhythm of life—my inner world reflecting the seasons of the outer one. Whatever it is, these last couple of months have been filled with what I’ll call creative weariness.

Since finishing the first draft of my third book, a force seems to have sapped all my creative energy. Every word I write feels forced, and every word I edit is painful. Every day, I show up to, and leave, the page, seriously considering whether to abandon the project entirely.

Part of this, I suspect, is because I have also been trying to figure out how to promote my writing (my books and this newsletter) on what I’ll call discoverability platforms—Twitter, Instagram, etc. Even typing the word “promote” makes me feel egocentric. This cascades into feelings that I’m no real artist at all… that the only reason I’m doing any of this is to gain attention and applause and status.

Thus, the source of creative weariness is revealed. Caught somewhere between the competing tensions of believing I have a message worth broadcasting and believing I’d be better suited leaving the job to others, my spirit is frayed.

But one of the benefits of doing these essays for over a year now is that I can look back at past works and understand that this feeling I’m in now has come and gone before. Having moved through a few seasons of undulating creative energy, I know enough now to understand that progressing through these periods requires finding resources to draw strength from.

Two of those resources for me are Paul’s Letters in the Bible and Screwtape Letters by C.S. Lewis, each of which I touch on in the remainder of today’s essay on creative weariness.]

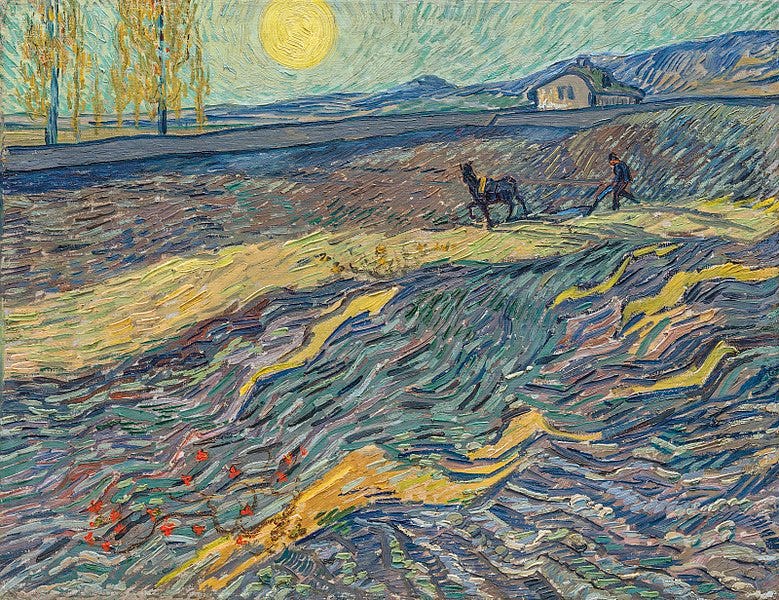

During his time in South France, Vincent Van Gogh (born 1853) produced over 2,100 pieces of art. In 1890, Van Gogh sold The Red Vineyard to fellow painter Ann Boch for 400 francs (roughly $20 today). It was the only time Van Gogh successfully sold a painting in a gallery and received a receipt. Convinced he was a failure and struggling with mental illness, Van Gogh committed suicide later that year. In 2017, one of his paintings (Labourer in a Field) sold for more than $81 million.

It seems to be a characteristic feature of many creative giants throughout the years to have labored in relative obscurity only to be recognized posthumously. Van Gogh, Bach, Kafka, Thoreau, Galileo, Poe, Oscar Wilde, and many more I’m sure I’m missing—all artists who did not live to see the world recognize their work as the masterpieces we now know them as. I don’t say this to suggest that I belong among that order of greats whose work went (relatively) unknown; I say this as a reminder of how often the times are poor judges of what’s timeless (making them unreliable proxies for determining the value or impact of our art).

If they were as human as we are, it’s easy to imagine how they—some of the best artists who ever lived—must have wrestled with the same self-doubts that we still face today. “Am I any good? Am I making any progress or impact at all? Is there any purpose or point to my labors? Will my sacrifices have any significance or make any sort of meaningful difference? Or am I being delusional and selfish?”

We’re left to wonder: how did they deal with the world not validating what they were doing? Were they purely intrinsically motivated and immune to doubt? Or did they, like Van Gogh, struggle with self-worth and fall sick when they didn’t receive acceptance from the world? How would they fare in today’s world of social media?

All questions that help us understand the lives of the greats are both inspirations and cautionary tales. Inspirational insofar as they could continue in their work regardless of how the world received it. Yet cautionary insofar as they reflect, as with Van Gogh, the dangers of weighing our worth on the scales of external approval (which increasingly depends on the favor of algorithms).

But for all this reflection on the motivations of creativity, none of this answers how, whether, and to what extent we ought to be doing it in the first place. For that, we must search elsewhere. This brings us to Paul’s letter to the Galatians (and the inner dialogue that ensues):

For if anyone thinks himself to be something being nothing, he deceives himself. But let each test his own work, and then he will have the ground of boasting in himself alone, and not in another. For each shall bear his own load. Now let the one being taught in the word share in all good things with the one teaching. Do not be misled: God is not mocked. For whatever a man might sow, that also he will reap. For the one sowing to his own flesh, from the flesh will reap decay. But the one sowing to the Spirit, from the Spirit will reap eternal life. And we should not grow weary in well-doing. For in due time we will reap a harvest, not giving up.1

First line: “For if anyone thinks himself to be something [when he is] nothing, he deceives himself.” This, my friends, is my chief concern. That I am, in fact, a nothing telling himself he’s something and it’s time I stopped kidding myself. It’s time to pack it in and return to a life of silence.

But then we arrive at the last line: “And we should not grow weary in well-doing. For in due time we will reap a harvest, not giving up.” Unlike the first line, this last line encourages me to endure in my efforts. Maybe the voice that wants me to stand down is the voice of Resistance. “So [does] my weary courage surge again, / and such sweet boldness rushed into my heart… turned me to our first intention—go!” ”2

Caught between these two competing forces, my spirit grows strained. I turn my heart toward the eternal and ask: Which is it? Do I side with the first voice or the second? Do I abandon my creative projects or continue?

Answer: Both. And neither.

The first line is right to the extent that it is a recognition that I (as in the ego) am, indeed, nothing (as He is everything). It is right to convict me of selfishness on occasion and put me back in my place. If I’m doing this whole thing right, nothing I do as a creative comes from me. To do something for personal attention is to betray the Muse I am to obey. And to desire recognition or approval for something that does not originate with me is to desire credit for something not of my doing. In that respect, the words of the first are right. It is only the voice in my head that reads in the extra suggestions that I have no talents or treasures worth sharing where this line goes wrong.

The last line is right to the extent that what I am doing is well-doing and sowing to the Spirit (rather than sowing to the flesh). To the extent that I sow to my own flesh, my flesh will reap decay, and failure is inevitable. To the extent I sow to the Spirit, failure is impossible and success inevitable. It all rests on sitting with myself and honestly asking whether I channel what wants to move through me or allow my ego to obstruct the flow.

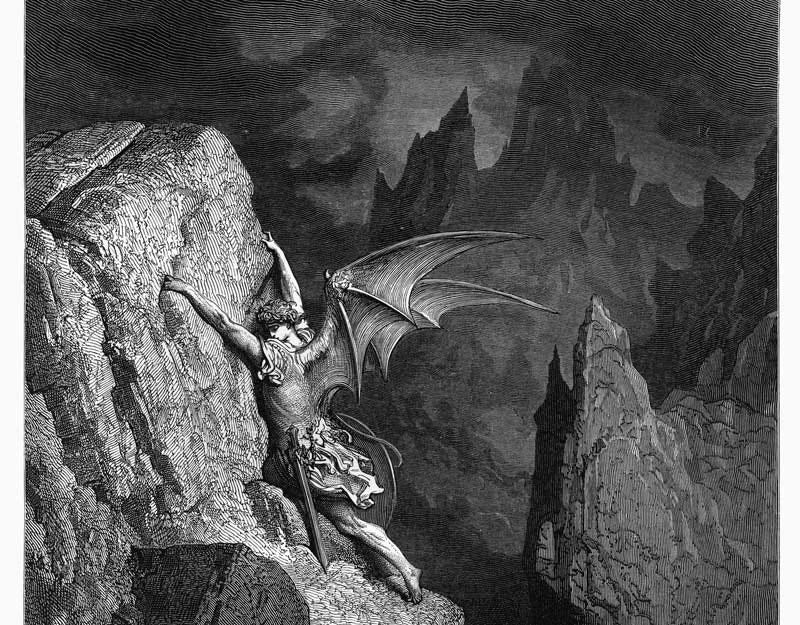

As long as I can be still and know that I am serving the Spirit, I can know all suggestions of abandonment come from that eternal anti-spirit that exists to deny all creative efforts. It is the spirit called Resistance and Screwtape I spoke about in On the Spirit That Denies. Its best work is taking virtues and twisting them into vices. Here, I am reminded that humility is a virtue; timidity is an illness.

Whenever I find myself fighting the force that negates, I return to Screwtape Letters by C.S. Lewis in an effort to know my enemy. On the topic of my current creative weariness, I find Screwtape’s words to Wormwood on how to exploit fatigue in his efforts to win human souls for Hell particularly instructive:

Whatever he says, let his inner resolution be not to bear whatever comes to him, but to bear it ‘for a reasonable period’—and let the reasonable period be shorter than the trial is likely to last. It need not be much shorter; in attacks on patience, chastity, and fortitude, the fun is to make the man yield just when (had he but known it) relief was almost in sight.3

—

There you have it, my friends. My message to you is my message to me. Sow to the Spirit. Create for eternity. In those efforts, “be steadfast, immovable, always abounding in the work of the Lord, knowing that your toil in the Lord is not in vain.” ”4 Be unyielding.

Spring is coming.

Galatians 6:3-9.

Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy, lines 130-137.

C.S. Lewis, Screwtape Letters, p. 167.

1 Corinthians 15:58.

It’s all about flow. Getting back to flow and ignoring the disrupters. Appreciate your insight and gentle reminder of where focus should remain if we want to progress🙏🏼❤️

Thank you for this. Struggeling, questioming, wanting to throw away a creative work is so easy. But even if in the world it will not be worth anything, in the end, it is soul-food. It will be worth something to you. ♥️✨️